From the September 2024 concern

A problem known as the final word parsec downside detailed the theoretical difficulty in bringing supermassive black holes shut ample for gravitational waves to carry away momentum and set off them to lastly merge.

A screenshot from a simulation reveals two merging supermassive black holes. Credit score rating: NASA’s Goddard Home Flight Center/Scott Noble; simulation data, d’Ascoli et al. 2018

“The great hum” inside the October 2023 concern states that astronomers weren’t sure that supermassive black holes in binary strategies might shut in on each other. I might assume that objects with such big gravity would utterly entice each other over time and finally merge. What am I missing?

Bill Ziegler

West Chicago, Illinois

All big galaxies are believed to host supermassive black holes tons of of 1000’s or billions of situations the mass of the Photo voltaic. When galaxies merge — which everyone knows they do, and sometimes — it seems a foregone conclusion that their supermassive black holes (SMBHs) should additionally merge. In any case, we have got seen smaller stellar-mass black holes merge. Nonetheless the physics involved in the best way wherein SMBHs lastly technique each other sooner than merging will get barely powerful. This conundrum is often known as the final word parsec downside, and it’s plagued astrophysicists as a result of the Eighties.

Let’s start with two merging galaxies. Each has an SMBH. As a result of the galaxies entwine, they finally kind a single galaxy made up of the combined supplies — along with stars, gasoline, and black holes — of the two progenitors. As points settle, the two SMBHs, as quickly as in the middle of their respective galaxies, begin to work their means in direction of the center of the final word galaxy as successfully. They obtain this via a course of known as dynamical friction, moreover known as gravitational drag. As a result of the black holes encounter shut by stars and gasoline, sometimes instead of falling into the SMBH, the star or gasoline cloud instead will get a gravitational improve. Mainly, they’re slingshot away from the SMBH, similar to a spacecraft that makes use of planetary gravitational assists to maneuver via the picture voltaic system. Giving a star or gasoline some vitality robs the SMBH of a tiny little little bit of its private, lowering its momentum.

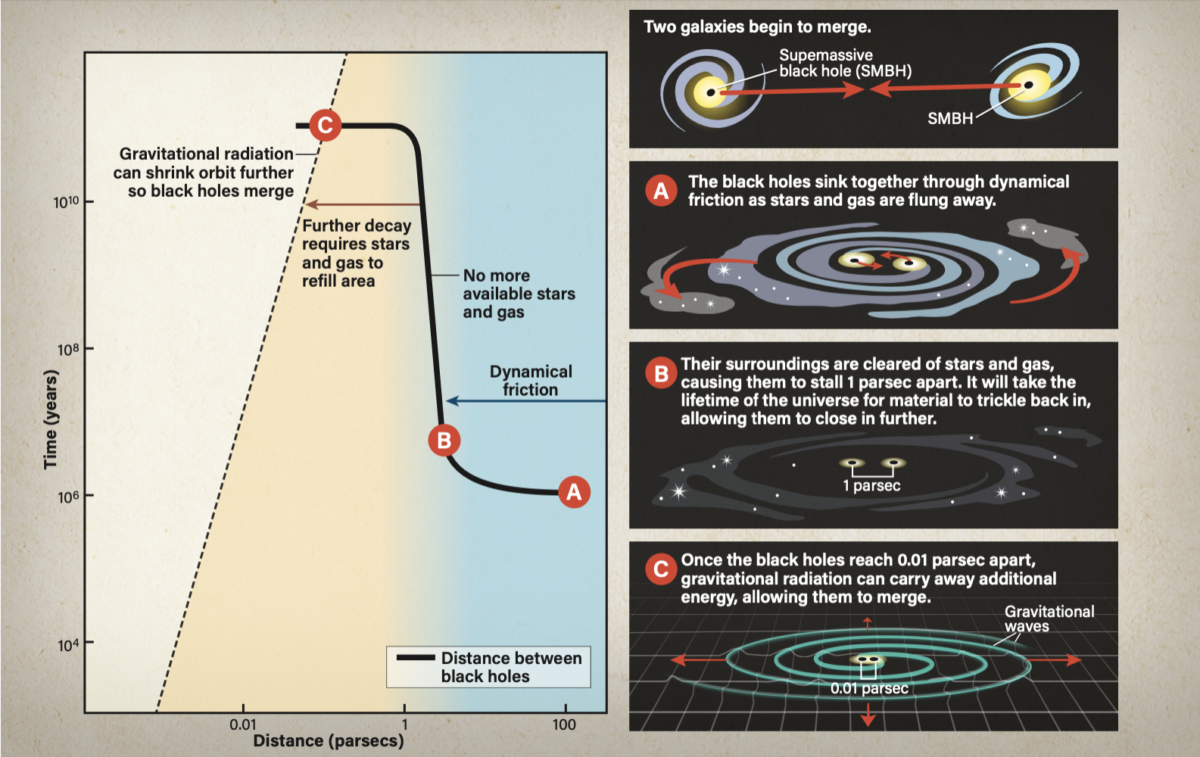

In the end, dynamical friction brings every SMBHs to the galactic center they normally begin to orbit each other (stage A inside the diagram underneath). They proceed to lose momentum via dynamical friction for various billion years, until they close to a distance about 1 parsec (3.26 light-years) apart.

Then the tactic stalls out, bringing us to the “closing parsec” part of the problem. To reach this stage, the black holes might have cleared the world of stars and gasoline, leaving nothing for added interactions (stage B). It’s going to take the black holes some 10 billion additional years, mainly the age of the universe, for ample stars and gasoline to trickle once more into the world, refill it, and create ample drag though interactions to allow the black holes to cross the final word parsec and merge.

What about gravitational waves? These ripples in space-time carry vitality away from orbiting objects so that they are going to merge. Nonetheless for gravitational waves to carry away ample vitality for SMBHs to merge, these SMBHs ought to be at most 0.01 laptop computer apart. So, you see the problem — we understand one of the simplest ways to get SMBHs 1 laptop computer apart, nonetheless no nearer.

In June 2023, the NANOGrav crew of radio astronomers launched that they’d detected a background hum of low-frequency gravitational waves of the kind we predict could be generated by merging SMBHs. This suggests that there is a technique to convey SMBHs shut ample to lose vitality via gravitational waves and merge (stage C). Astronomers have various ideas about how the universe may overcome the final word parsec downside, notably by throwing a third SMBH into the mixture (which then will get kicked out of the system, depleting the two remaining SMBHs of great vitality). Or perhaps the calculations behind the tactic of SMBHs are oversimplified and totally different parts need to be considered.

The recently detected background hum cannot however be separated into its parts successfully ample to lastly say for sure whether or not or not we’re seeing merging SMBHs. Nonetheless astronomers strongly suspect that’s the case and now have an unimaginable jumping-off stage for finding that closing piece of robust proof that will current us the irrefutable merger of a pair of SMBHs.

Alison Klesman

Senior Editor